It was still raining when morning came. But we were not going to let that stop us. We enjoyed our breakfast, packed our backpacks, filled our water bottles, and got out our raingear. It would be the first time on the entire walk that we had to use them.

With the raingear on, we said goodbye to the other guests at the gite. We would not see them again. Then we stepped out into the morning air. By now, the rain was light, what we in Ireland would call a soft day. We made our way along the lanes back to the main road and headed for St. Etienne. The trail follows the road almost all the way, except for a brief shortcut where the road twists and turns. The rain stopped before we reached St. Etienne, though the skies were still dark. But in St. Etienne, the rain started again. We had made the decision that if it was raining, we would take the road route to St-Jean-du-Gard rather than the official route across the hills. And so, when we came to the junction point, we took the road.

Of course, the weather gods were just playing with us, and we had only gone a few kilometres before the rain had stopped and it looked like it was finished for the day. The skies were still grey, but lighter than before. So after those few kilometres, it was possible to take off the raingear. It had done its work at that stage and had justified its inclusion in the backpack. The road follows the valley of the river Gardon de Mialet. This is a country of gorges among the hills, and the river had cut deep into the rocks of the valley. St. Etienne is in the department of Lozère, and that department takes good care with its roads. There were kilometre markers along the road, and we could count the distance as we went.

Stevenson wrote that he also followed the road alongside the Gardon de Mialet, but then ascended into the hills to reach the summit of St. Pierre. He wrote lyrically of the views from that mountain. But when we looked up at the heights, they were still enveloped in cloud. So we kept to the road.

Eventually, the road crosses from the department of Lozère to the department of Gard. Gard does not take quite the same care with their roads, and there were no more kilometre markers along the way. We could only very roughly estimate how far we had come or how far we had to go. But we kept going. For a while, the noise of a chainsaw across the river disturbed the quiet. Now and then, cars and vans would pass in one direction or the other. But for the most part, it was a quiet journey along one of France’s backroads.

The road goes downhill into St-Jean-du-Gard, arriving in the town on what is the outward track of the Chemin de Stevenson. We went on into town, looking for somewhere that we could have lunch. After dropping our rucksacks at a café, we went inside. The proprietor told us he could not serve us because our rucksacks were at a table of the café next door. The café next door could serve us food, but no beer. Dismayed by this lack of welcome, we went back to a shopping centre on the way in, and there we found the mobile restaurant run by Sam and Isa. The restaurant comprises a catering wagon, with tables and chairs to the front, and waste receptacles off to the side. We settled for burgers and beers. They asked where we were from, as had so many others, and we told them. This was street food, French style. As we sat there, we could see that the two ladies enjoy a regular clientele. We speculated as to which was Sam and which was Isa, but without any definite conclusion.

St-Jean-du-Gard was the final destination for Stevenson on his journey. His writing suggests that he was in a hurry to finish. He speaks of being eager to reach Alès, which he calls Alais. And while he went into great detail about his purchase of Modestine in Monastier, he deals with her sale in in St. Jean in just one paragraph. Perhaps he was impressed by the palaver of the seller in Monastier and felt he could not equal that in his own description. But I doubt that this is the reason for so brief an account of her sale. His ending to the book seems rushed compared to the body of the work. Also, Stevenson gives no account of how he got to Alès. Since the book is an account of travels with a donkey, perhaps he felt no obligation to describe what happened before her arrival in his life, or after her departure.

In any case, we were not stopping in St. Jean, not even for the night. We were going on to Mialet. My guidebook, dated 2020, shows Mialet to be off the route, as it goes well to the north of that village. But Joff’s more recent guidebook showed that the route had been changed to go through Mialet. We left St. Jean after our lunch. The route goes up hill, but not strenuously so, leaving the town, and once more going into the forest. Somewhere along the way, after entering the forest, we found ourselves being accompanied by a black dog. He would run a little ahead of us, then stop and wait for us to catch up before he would run on again. Nothing we did seemed to shake him off. We tried hiding in bushes at the side of the trail, but he came back and found us, and then went on in front again. We tried telling him to go home, but without success. He had joined near the edge of St. Jean, and we worried that he might not find his way back again. We also worried that people might think he was our dog. Eventually, coming close to Mialet, we managed to get ahead of him, and turning around, blocked his way, ordering him to go home. He looked disappointed, dejected even, but with head down, he headed back up the track. I can only hope that he found his way home. He had a collar and name tag, so he was clearly cared for by someone. But perhaps dogs have desires for adventure no less than humans, and this was his adventure for the day.

We came into Mialet across a stone bridge called the Pont des Camisards. It was built between 1714 and 1716, at the end of the Camisard wars. For almost the next two centuries, it was the only stone bridge across the Gardon de Mialet.

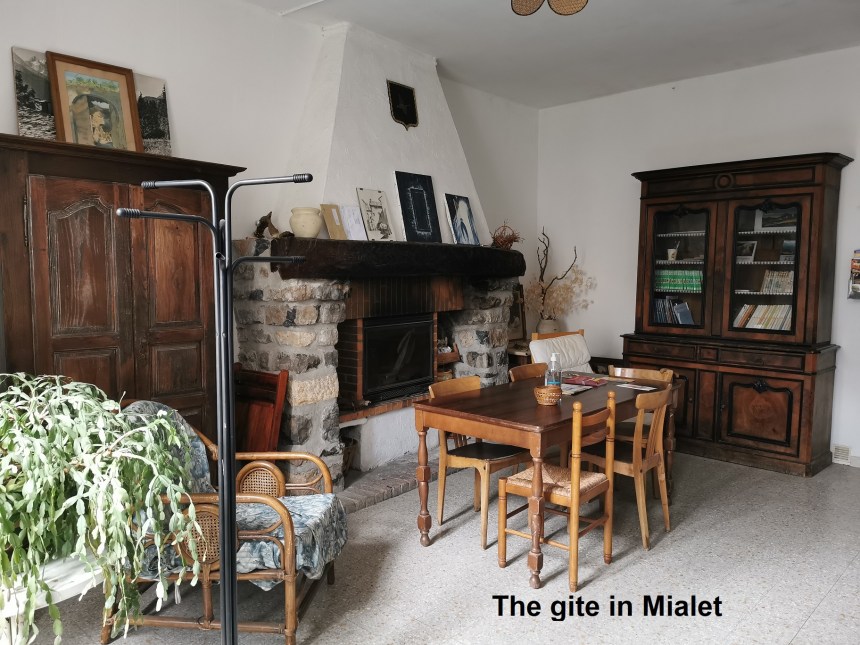

Once in the village, our next task was to find the gite that we had booked for the evening. We followed the road around to come to a small establishment claiming to be a restaurant and bar. When we asked where was the gite, he proprietor very kindly left his work and offered to walk the short distance up the street with us, about fifty metres. He explained that we needed to be careful on this street, because although it was only six or seven metres wide, it was officially classified as an avenue, He asked if I understood what that meant. You mean like the Champs Elysée, I replied with a smile. Exactly, he laughed. And then we were at the gite.

This gite was effectively unstaffed, but it had a volunteer guardian who showed us to our room. He explained the system to us. There was a small pantry with food priced for sale. It worked on an honour system, with an open cashbox nearby. He explained that we could also buy food in the bar, which was also an épicerie. So back to the bar we went and got some food. While we were in the little épicerie, it started to rain, very soon there was a violent thunderstorm in full swing. We had no choice but to wait it out, enjoying a beer while waiting.

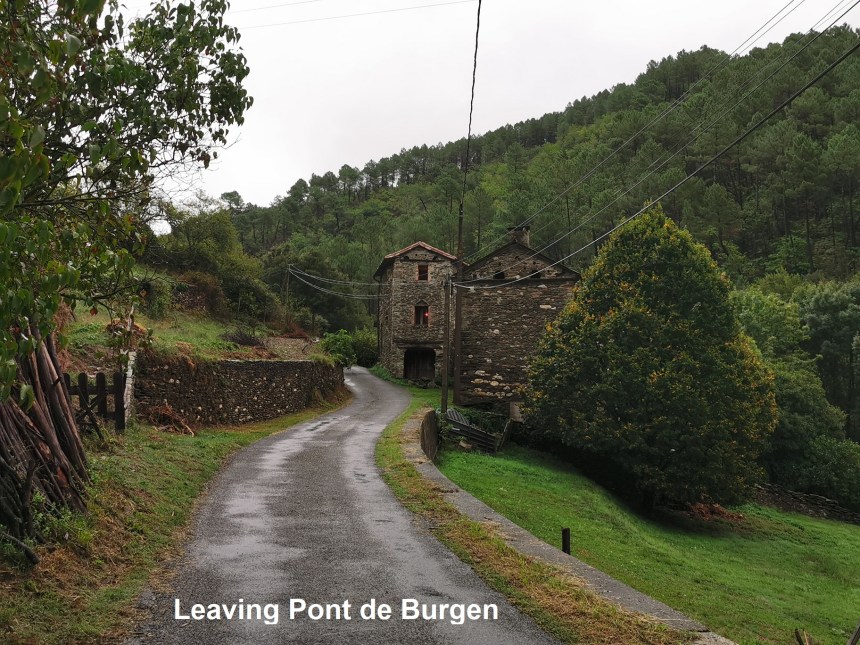

The storm, though intense, did not last long, and we went back to the gite. Cooking was delayed by a problem with the gas cooker, but it was eventually sorted out by Joff and one of the other guests. Joff cooked up dinner, and we ate well. There were eight of us there in the gite, each couple cooking for themselves. While the gite was pleasant, it lacked the convivial atmosphere of the Pont de Burgen. We each washed up as well, returning crockery and pans to their places, and everyone retired for the night.

Joff remarked that we were coming to the end of his guidebook. You will have to get a new guidebook then, I replied. This adventure is not the end, I told him, there will be others.